University of Oxford

History of Science Museum

“‘I’m sorry about the clock,’ he said.

‘It’s an old clock,’ I told them idiotically.

I think we all believed for a moment that it had smashed in pieces on the floor.”

Vacheron deck watch from storied D-Day cruiser, HMS Belfast

Denis Bartel, the “Desert Walker” enjoying refreshments with his wife after a long walk in the Simpson Desert—with his Omega Speedmaster visible on his wrist

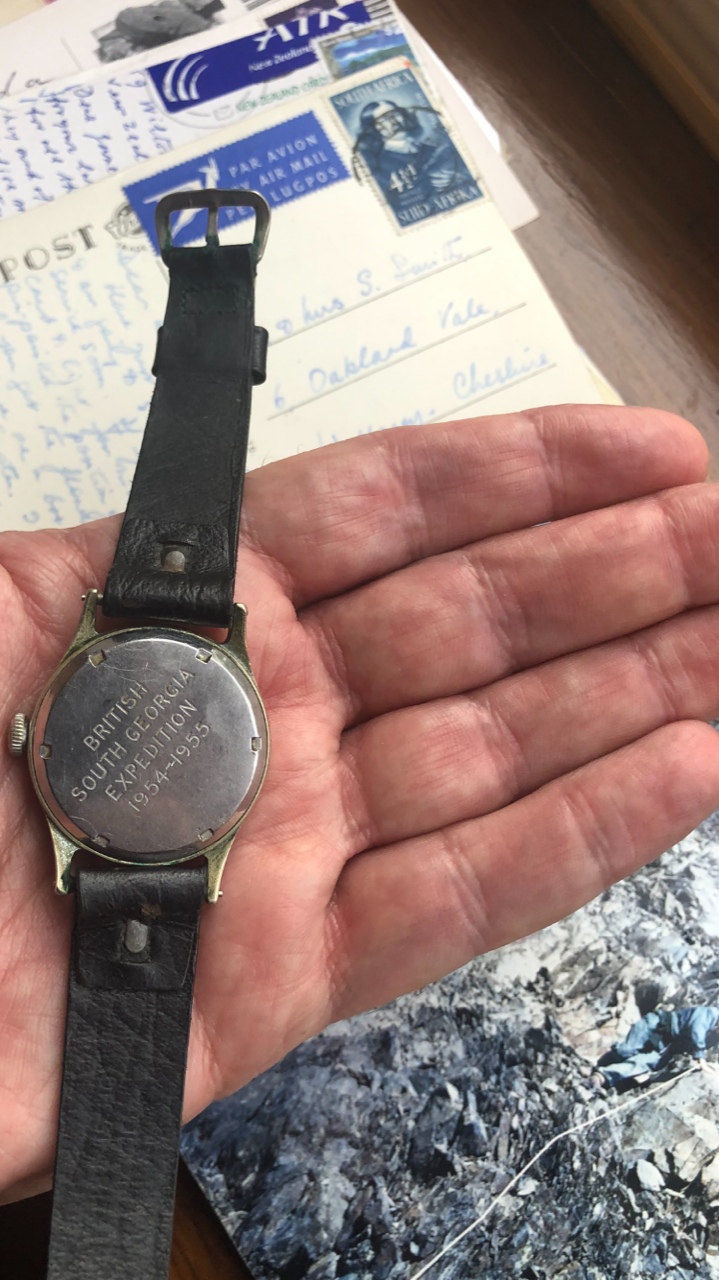

George Sutton in South Georgia

Countess Marie Larisch's Patek that may have helped start World War I

Timepieces, from sundials to atomic clocks, are so fully merged with the unique concept they represent that is hard to view them as either tangible or intangible; rather, they stand between the two, and so may be called pantangible. Without methods for measuring and tracking time, we lose the ability to appreciate its passage. Simply put, unless measured, time loses its meaning. A clock or calendar, therefore, is not just a device for measuring time, it is an expression of the human conception of time. It is for these reasons that, since the beginning of time, humanity has exerted so much effort, scientific expertise and resource on the enterprise of timekeeping. It is also why timepieces themselves, from Big Ben to John Harrison’s H4 chronometer, have become freighted cultural repositories in their own right.

In recognition of the close connection between time and heritage, and to acknowledge the history that timekeepers often embody, the IDA, in collaboration with the History of Science Museum and the world’s oldest watchmaker, Vacheron Constantin, will explore and celebrate both the science and the philosophy of time through the upcoming installation, The Heartbeat of the City: 500 Years of Personal Time. Marking 500 years of wearable timepieces, the installation also celebrates the 1000th anniversary of the mechanical clock and the upcoming centennial of Albert Einstein’s Nobel Prize. It is a propitious moment to think about our connection to time and the extraordinary devices that measure its passage.

The installation is centered around a monumental kinetic sculpture eponymously entitled Heartbeat of the City. It is based on the design of Thomas Mudge’s historic timepiece—Queen Charlotte’s watch of 1770—that incorporated one of mankind’s most important and enduring engineering achievements, the lever escapement—the magical device that lies at the heart of most every mechanical wristwatch. The mechanism within this fascinating new sculpture literally derives its tempo from the vibrations of the city in which it stands and the visitors who come to see it. In this way, its design reminds us of the inextricable link between the concept of time and those who seek to measure it. It reminds us that time would be meaningless without reference to the people whose lives, loves, struggles and accomplishments fill time with meaning. Even as time symbolizes our own mortality, it is human beings that give life to time.

Heartbeat of the City: 500 Years of Personal Time could not have found a better home than Oxford’s History of Science Museum. Its collections tell the story of the very foundations of modern science. Among these riches are many intriguing objects that chart the development of time-telling from antiquity to the early modern world, including its crucial link to astronomy. The museum houses the world’s finest collections of astrolabes and sundials from Europe and the Near East, including a rare portable Roman sundial. The Museum also holds a number of significant early clocks and watches. Particularly notable is an early and unmodified pendulum clock from about 1665 by England’s first clock-maker, Thomas Tompion.

A substantial number of these objects were given by the Museum’s founding donor, Lewis Evans, whose scientific collections enabled the 1924 establishment of the Museum. In addition to this founding collection, in 1966, the Museum acquired the historic collection of the antiquarian horologist Cyril Beeson (1889–1975). Beeson’s collection focused on Oxfordshire clocks, including turret, lantern and longcase clocks. In honor of this donation, the “Beeson Room,” a space within the Museum’s historic Broad Street building, was created to display and interpret many of these local clocks. These collections, together with the sculpture, Heartbeat of the City, and special timepieces from the Vacheron Constantin and IDA collections, will not only help visitors explore milestones in man’s engagement with time, but also suggest a framework for appreciating how time gives shape and substance to history.

Alexy Karenowska, IDA Director of Technology

Roger Michel, IDA Executive Director

Visit Us

History of Science Museum

Broad St.

Oxford, OX1 3AZ

Hours

Tuesday - Sunday

12pm - 5pm

Contact Us

+44 1865 277 293

info@hsm.ox.ac.uk

Please note that as a COVID-19 precaution, a timed ticket is required for entry. You can book your free ticket HERE.